Let your imagination back out of the box

- Apr 21, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Sep 22, 2025

A few loose thoughts on the role art and creativity play in my research

Heads up: I’m switching gears a bit this week (shifting topics away from my usual themes of academic/scholarly writing, scicomm, and making academia a better place).

While I haven’t written about it much recently (though I have an extensive archive on the subject), creativity plays a huge role in how I experience the world and in how I approach my work as an academic. Specifically, I make art to notice, record, and play in the world, to keep me human, to stay connected to the more-than-human. And, I use arts practices to inform my hands-on teaching methods, enhance the tool kits of scientists I teach and coach, and even to study improved ways to teach field and lab classes. I also tap a lot of creative writing approaches to inform my writing and the writing support I offer. [1] And I rely on my experience with arts organizations to enhance how I conceptualize and facilitate everything from strategic planning to grant writing.

I do so because creativity is vital to science. And, because artistic and creative expression are fundamental to humans, and such activities date back to the earliest activities of our species. In fact, for some people, art (regardless of the “quality” of your output) feels inevitable.

For instance, I’ve been pursuing creative expression in many forms since I was pretty young: sketching cartoon characters, illustrating “books,” sewing, learning to play multiple instruments, etc.

Likewise, think of virtually any child you know. What do they do? They draw and create things, they imagine and invent. They conjure worlds and monsters and magic out of modeling clay and rubber bands, with mountains of scotch tape and cardboard. They dance, improvise songs, and make profound and comic pronouncements that are pure poetry.

As we grow up, though, our free flowing imaginations get boxed in by external pressure to make art that “makes sense,” “looks like something,” demonstrates at least amateur proficiency, and can be commercialized1. In other words, the human instinct to respond to the world, our emotions, and each other—by making creative images, gestures, and sounds—gets stuffed into a box. And if our impulses to create don’t fit in the box, those impulses get shut down completely.

Perhaps fortunately (?) for me, my impulses fit in the box. For years I made art that was representative (“looked like” something, rhymed, etc.). So, my interest was fostered (albeit as a hobby). But, I never agreed that I should decide and focus on just one thing. My rejection of narrowing my interests was an attitude—especially for a first-generation kid—that definitely didn’t fit in the box.

When I was in high school, I took all the math and science classes available in my small, rural school (which was far more of any of those subjects than was expected). I also took all the art and music classes, drew a logo for our high school, and won the senior art award decided by the local artists guild. [2] In college, I became a paid artist through a work study position to illustrate benthic macroinvertebrates [3], design a logo, and create a field journal lesson (all for a watershed education nonprofit). I also began teaching other people to draw as a way of focusing and learning about the natural world. Long before I learned the acronym STEAM, I resisted choosing between STEM and art.

It wasn’t until I left my home state in my mid-twenties, however, that I started to really appreciate art for art’s sake, not exclusively as a communicative or learning tool (or paying side hustle) that reflected back to me a world I already could see and learned to understand. Which is to say, I began to interact more with modern art museums and performances. These experiences taught me to appreciate abstract art, conceptual art, folk art, modern jazz, global music, etc. In my own art, I branched out beyond sketching, watercolor painting, and photography to fiber arts, found art, and much funkier, weirder versions of the traditional mediums I’d worked in previously.

At the same time, I was learning a ton about ecology research, science manuscript editing, and science journalism. Indeed, for a while those three activities became my primary ways of making a living. No surprise, then, that I began mashing all these ideas up in my art.

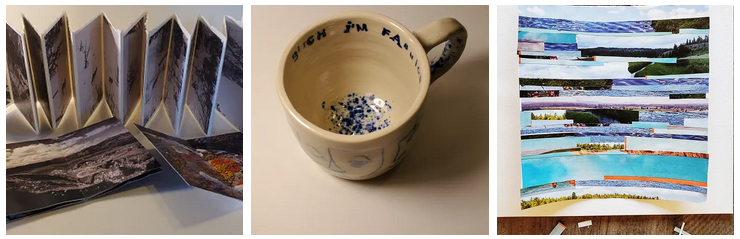

Then, I moved to where I am now—the high, windswept plains of southeast Wyoming. Here, I encountered modern poetry, indie fiction, and nonfiction that wasn’t just nature writing. These types of literature added another layer of complexity and quirkiness to my understanding of the world and the ways I could interact and react to it creatively and scientifically. I also learned about book making and returned to ceramics.

These days, I still draw and paint and take photographs. But I also do collages, make pottery and art books, contribute to public art, and write poetry. And, I pull a lot of the underlying practices of these art forms into my teaching, writing, and research. Indeed, I’m increasingly offering (and studying impacts of) workshops, trainings, and courses that leverage these ideas for the benefit of STEM research, multi-disciplinary grant writing, and more.

This mash-up makes my life invigorating and meaningful. I am not just privileged to be an academic (though that is a privilege itself). I am privileged to be an academic because the self-determination intrinsic in faculty positions leaves me room to do a lot of things my way. And my way is to weave my arts and science practices together into a conceptual and experiential tapestry. At so many points in my life, people told me I needed to choose between art and science. The subtext was: choose science, at least you’ll get paid. [4] But, if I had chosen only one, I wouldn’t understand the world in such multidimensional ways. Instead, I embraced a carnival of ways of thinking and expressing. Because of this, my art and science work is far more vibrant than would be possible if I simply did one or the other in isolation.

How about you?

What are the sources of inspiration and creativity that you tap for your personal and professional interactions with the world and other people?

[1] My book with Stephen Heard—Teaching and Mentoring Writers in the Sciences—is available now for pre-order from University of Chicago Press! Use UCPNEW for 30% off copies you order for yourself, friends, and mentees!

[2] My purple ribbon was stolen from the public art display, because I was not one of the popular kids who our peers thought ought to have won. (An early lesson in not letting others define your value or metrics of success.)

[3] And inadvertently thereby reckoned with my deep-seated arachnophobia. Staring for hours into a microscope at invertebrate specimens quickly desensitized me!

[4] We have a toxic, cultural expectation that artists should be passionate enough about their art to work for free or very little. As I’ve written, this “passion career” toxicity has crept into science and academia, to the detriment of all three sectors.

Comments